| CHARLES DOBIE : GENEALOGY DOBIE and RUST-D'EYE |

|---|

Opera Atelier

Opera AtelierForget Mrs. Bates. Turn the page on Dolores Claibome. Say goodbye to Pink Flamingoes. And bid a wary welcome back to the scariest murderess of them all: Medea.

Spumed in love, this half-human sorceress of ancient Greek myth destroys everything in her path before being whisked away in a blast of wind.

How this carnage comes to be is one of the best stories ever told, full of high adventure, court intrigue, lust, passion, duplicity and revenge.

It's the stuff of great theatre

Audiences familiar with Opera Atelier know that co-artistic directors Marshall Pynkoski and Jeannette Zingg, along with world-class singers and dancers, and the Tafelmusik Baroque Orchestra and Chorus, deliver music as polished as the staging.

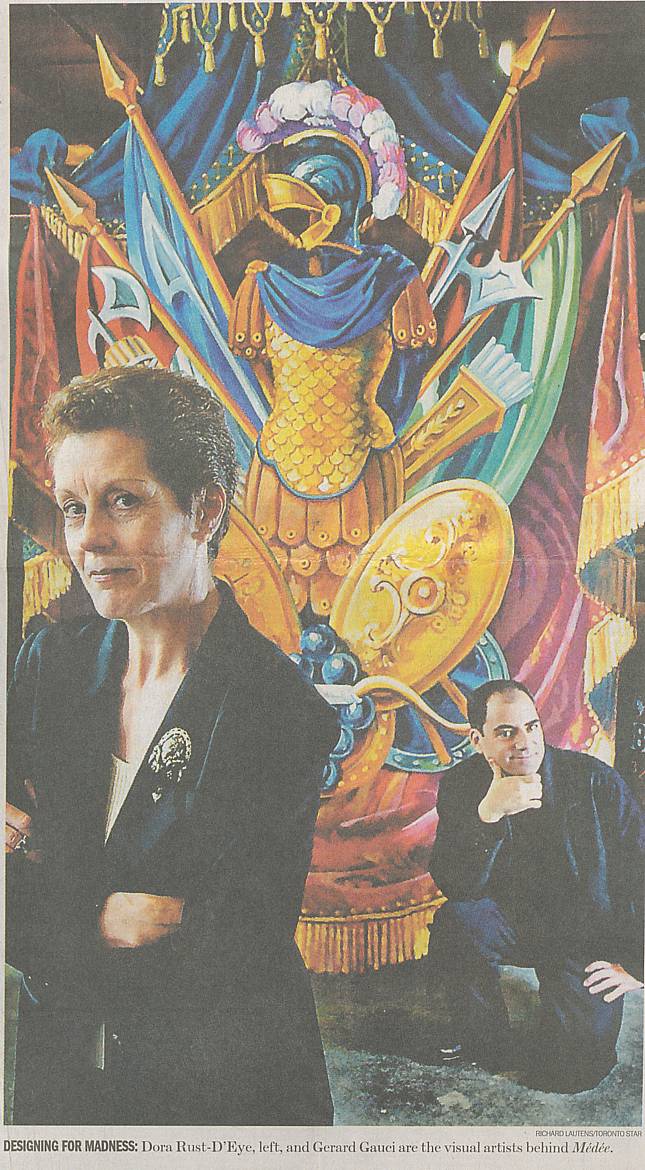

And their productions are always a visual treat, thanks to the the work of set designer Gerard Gauci and costume designer Dora Rust-D'Eye.

An early morning spent in

their company recently highlighted the importance of their

collaboration

Pynkoski says that even if all the original set and costume designs were available, this would only be a jumping-off point for Opera Atelier. "We've always argued and tried to help people understand we are not a museum company; we are not trying to reproduce something exactly as it happened."

The director says they are not historians, but artists, "so that Dora is creating new costumes that no one ever saw in a production of Médée."

Adds Gauci: "We've all spent 20 years learning the vocabulary. Now, at this stage of the game, we can create very freely within that. I'll go away and create designs that are in that spirit but are all original designs."

Gauci, who is an associate at the Ontario College of Art and Design and an established visual artist in his own right, pulls out detailed sketch-size paintings of each scenic backdrop and points to the influence of Roman design, while also making historical references to the original Baroque sets.

The resulting new look, while still rich in colour and detail, is less fussy. "There is somewhat of a modern take on these designs as everything gets stripped down, so that we can focus attention on performers standing in front of this thing," says Gauci.

In Médée, paring down also means there will be no big white powdered wigs because, as Pynkoski says, the actors get physical in this production, clutching their heads and pulling at their hair. "The actors are telling the story with their bodies, and the wigs get in the way.

"Maybe there'll be a less fraught

production a few years from now and

no one will be pulling their hair

"Better they mess up their hair than their costumes,"interjects Rust-D'Eye, whose work as Opera Atelier's original costume designer has brought her international recognition, including an exhibit at the Victoria And Albert Museum in London.

Unlike Gauci's mini renderings, the costume designer's first costume is her first sketch, on the body of a real person, "usually Jeanette (Zingg), because she lives here."

"Sometimes I have no clue where I'm going with a costume until I start working with it. And then I just pull fabrics and decoration and work with the fabric."

This is a time-consuming practice

Gauci has worked with the same painters for several years. "I have to pander to them," he says. "They're such fine painters that I have nightmares of them deciding to do something else with their lives. I now know that they can reproduce my designs exactly to the scale I want. And for this to happen, I need to give them four months."

"What I like about our productions is that they never look over-designed," says Pynkoski, when asked about how the creative team works together.

"No one suddenly pulls a fast one and does something bizarre. We're all seeking our inspiration in the story," he adds, emphasizing the group's great familiarity with the Baroque aesthetic vocabulary.

"But we do get unexpected suprises on stage," Gauci says, describing how he "designed a red boudoir for (The Coronation Of Poppea), not knowing that Dora was using red for the costumes. In the end this wrapped (Poppea) in this conceptual womb that I would never have thought of. And it worked."

Rust D'Eye adds, "Gerard and I will often sit through dress rehearsal and go 'Wow! Look at that colour!'"

The audience probably has the same reaction, which only helps heighten the drama of the story itself.

In a nutshell, Jason

Baroque opera drew liberally from such juicy myths, and Charpentier's effort, dedicated to French king Louis XTV and premiered at the Paris Opera in 1693, is a five-act epic brimming with masterful musical shading and contrast.

"It's so moving and so sad," says Pynkoski. "It's such a gut-wrenching story. Like all those great mythic stories, we know what the problem is, what's going to happen and we sit there with bated breath to see how it's all going to play out."

The musicians are led by French

conductor Hervé Niquet, and the title

role is being sung by American mezzo-soprano Stephanie Novacek

Other notables are counter-tenor Cyril Auvity as Jason, Nathalie Paulin as Créuse, Alain Coulombe as Créon, Olivier Laquerre as Oronte and Krisztina Szabo as Nérine.

The opera is being sung in its original French, and runs to Nov. 10.

| HOME | DOBIE | TOP |

|---|